Handling relocations

In the previous post, we learned how to parse an object file and import and execute some functions from it. However, the functions in our toy object file were simple and self-contained: they computed their output solely based on their inputs and didn't have any external code or data dependencies. In this post we will build upon the code from part 1, exploring additional steps needed to handle code with some dependencies.

As an example, we may notice that we can actually rewrite our add10 function using our add5 function:

obj.c:

int add5(int num)

{

return num + 5;

}

int add10(int num)

{

num = add5(num);

return add5(num);

}

Let's recompile the object file and try to use it as a library with our loader program:

$ gcc -c obj.c

$ ./loader

Executing add5...

add5(42) = 47

Executing add10...

add10(42) = 42

Whoa! Something is not right here. add5 still produces the correct result, but add10 does not . Depending on your environment and code composition, you may even see the loader program crashing instead of outputting incorrect results. To understand what happened, let's investigate the machine code generated by the compiler. We can do that by asking the objdump tool to disassemble the .text section from our obj.o:

$ objdump --disassemble --section=.text obj.o

obj.o: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000000 <add5>:

0: 55 push %rbp

1: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

4: 89 7d fc mov %edi,-0x4(%rbp)

7: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

a: 83 c0 05 add $0x5,%eax

d: 5d pop %rbp

e: c3 retq

000000000000000f <add10>:

f: 55 push %rbp

10: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

13: 48 83 ec 08 sub $0x8,%rsp

17: 89 7d fc mov %edi,-0x4(%rbp)

1a: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

1d: 89 c7 mov %eax,%edi

1f: e8 00 00 00 00 callq 24 <add10+0x15>

24: 89 45 fc mov %eax,-0x4(%rbp)

27: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

2a: 89 c7 mov %eax,%edi

2c: e8 00 00 00 00 callq 31 <add10+0x22>

31: c9 leaveq

32: c3 retq

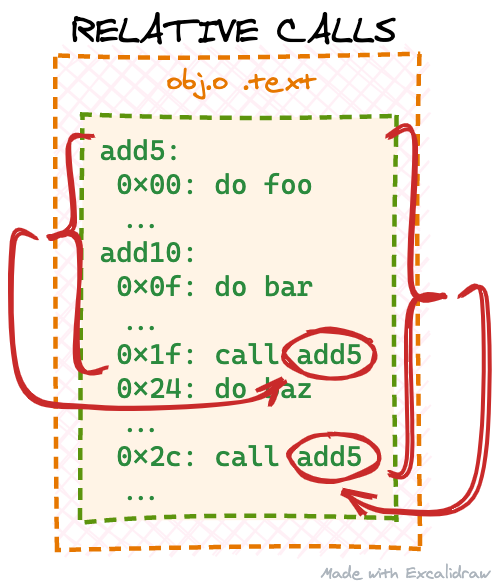

You don't have to understand the full output above. There are only two relevant lines here: 1f: e8 00 00 00 00 and 2c: e8 00 00 00 00. These correspond to the two add5 function invocations we have in the source code and objdump even conveniently decodes the instruction for us as callq. By looking at descriptions of the callq instruction online (like this one), we can further see we're dealing with a "near, relative call", because of the 0xe8 prefix:

Call near, relative, displacement relative to next instruction.

According to the description, this variant of the callq instruction consists of 5 bytes: the 0xe8 prefix and a 4-byte (32 bit) argument. This is where "relative" comes from: the argument should contain the “distance” between the function we want to call and the current position — because the way how x86 works this distance is calculated from the next instruction and not our current callq instruction. objdump conveniently outputs each machine instruction's offset in the output above, so we can easily calculate the needed argument. For example, for the first callq instruction (1f: e8 00 00 00 00) the next instruction is at offset 0x24. We know we should be calling the add5 function, which starts at offset 0x0 (beginning of our .text section). So the relative offset is 0x0 - 0x24 = -0x24. Notice, we have a negative argument, because the add5 function is located before our calling instruction, so we would be instructing the CPU to "jump backwards" from its current position. Lastly, we have to remember that negative numbers — at least on x86 systems — are presented by their two's complements, so a 4-byte (32 bit) representation of -0x24 would be 0xffffffdc. In the same way we can calculate the callq argument for the second add5 call: 0x0 - 0x31 = -0x31, two's complement - 0xffffffcf:

It seems the compiler does not generate the right callq arguments for us. We've calculated the expected arguments to be 0xffffffdc and 0xffffffcf, but the compiler has just left 0x00000000 in both places. Let's check first if our expectations are correct by patching our loaded .text copy before trying to execute it:

loader.c:

...

static void parse_obj(void)

{

...

/* copy the contents of `.text` section from the ELF file */

memcpy(text_runtime_base, obj.base + text_hdr->sh_offset, text_hdr->sh_size);

/* the first add5 callq argument is located at offset 0x20 and should be 0xffffffdc:

* 0x1f is the instruction offset + 1 byte instruction prefix

*/

*((uint32_t *)(text_runtime_base + 0x1f + 1)) = 0xffffffdc;

/* the second add5 callq argument is located at offset 0x2d and should be 0xffffffcf */

*((uint32_t *)(text_runtime_base + 0x2c + 1)) = 0xffffffcf;

/* make the `.text` copy readonly and executable */

if (mprotect(text_runtime_base, page_align(text_hdr->sh_size), PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC)) {

...

And now let's test it out:

$ gcc -o loader loader.c

$ ./loader

Executing add5...

add5(42) = 47

Executing add10...

add10(42) = 52

Clearly our monkey-patching helped: add10 executes fine now and produces the correct output. This means our expected callq arguments, which we calculated, are correct. So why did the compiler emit wrong callq arguments?

Relocations

The problem with our toy object file is that both functions are declared with external linkage — the default setting for all functions and global variables in C. And, although both functions are declared in the same file, the compiler is not sure where the add5 code will end up in the target binary. So the compiler avoids making any assumptions and doesn’t calculate the relative offset argument of the callq instructions. Let's verify this by removing our monkey patching and declaring the add5 function as static:

loader.c:

...

/* the first add5 callq argument is located at offset 0x20 and should be 0xffffffdc:

* 0x1f is the instruction offset + 1 byte instruction prefix

*/

/* *((uint32_t *)(text_runtime_base + 0x1f + 1)) = 0xffffffdc; */

/* the second add5 callq argument is located at offset 0x2d and should be 0xffffffcf */

/* *((uint32_t *)(text_runtime_base + 0x2c + 1)) = 0xffffffcf; */

...

obj.c:

/* int add5(int num) */

static int add5(int num)

...

Recompiling and disassembling obj.o gives us the following:

$ gcc -c obj.c

$ objdump --disassemble --section=.text obj.o

obj.o: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000000 <add5>:

0: 55 push %rbp

1: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

4: 89 7d fc mov %edi,-0x4(%rbp)

7: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

a: 83 c0 05 add $0x5,%eax

d: 5d pop %rbp

e: c3 retq

000000000000000f <add10>:

f: 55 push %rbp

10: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

13: 48 83 ec 08 sub $0x8,%rsp

17: 89 7d fc mov %edi,-0x4(%rbp)

1a: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

1d: 89 c7 mov %eax,%edi

1f: e8 dc ff ff ff callq 0 <add5>

24: 89 45 fc mov %eax,-0x4(%rbp)

27: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

2a: 89 c7 mov %eax,%edi

2c: e8 cf ff ff ff callq 0 <add5>

31: c9 leaveq

32: c3 retq

Because we re-declared the add5 function with internal linkage, the compiler is more confident now and calculates callq arguments correctly (note that x86 systems are little-endian, so multibyte numbers like 0xffffffdc will be represented with least significant byte first). We can double check this by recompiling and running our loader test tool:

$ gcc -o loader loader.c

$ ./loader

Executing add5...

add5(42) = 47

Executing add10...

add10(42) = 52

Even though the add5 function is declared as static, we can still call it from the loader tool, basically ignoring the fact that it is an "internal" function now. Because of this, the static keyword should not be used as a security feature to hide APIs from potential malicious users.

But let's step back and revert our add5 function in obj.c to the one with external linkage:

obj.c:

int add5(int num)

...

$ gcc -c obj.c

$ ./loader

Executing add5...

add5(42) = 47

Executing add10...

add10(42) = 42

As we have established above, the compiler did not compute proper callq arguments for us because it didn't have enough information. But later stages (namely the linker) will have that information, so instead the compiler leaves some clues on how to fix those arguments. These clues — or instructions for the later stages — are called relocations. We can inspect them with our friend, the readelf utility. Let's examine obj.o sections table again:

$ readelf --sections obj.o

There are 12 section headers, starting at offset 0x2b0:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000040

0000000000000033 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 1

[ 2] .rela.text RELA 0000000000000000 000001f0

0000000000000030 0000000000000018 I 9 1 8

[ 3] .data PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000073

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 1

[ 4] .bss NOBITS 0000000000000000 00000073

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 1

[ 5] .comment PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000073

000000000000001d 0000000000000001 MS 0 0 1

[ 6] .note.GNU-stack PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000090

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[ 7] .eh_frame PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000090

0000000000000058 0000000000000000 A 0 0 8

[ 8] .rela.eh_frame RELA 0000000000000000 00000220

0000000000000030 0000000000000018 I 9 7 8

[ 9] .symtab SYMTAB 0000000000000000 000000e8

00000000000000f0 0000000000000018 10 8 8

[10] .strtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 000001d8

0000000000000012 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[11] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00000250

0000000000000059 0000000000000000 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

l (large), p (processor specific)

We see that the compiler created a new section called .rela.text. By convention, a section with relocations for a section named .foo will be called .rela.foo, so we can see that the compiler created a section with relocations for the .text section. We can examine the relocations further:

$ readelf --relocs obj.o

Relocation section '.rela.text' at offset 0x1f0 contains 2 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

000000000020 000800000004 R_X86_64_PLT32 0000000000000000 add5 - 4

00000000002d 000800000004 R_X86_64_PLT32 0000000000000000 add5 - 4

Relocation section '.rela.eh_frame' at offset 0x220 contains 2 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

000000000020 000200000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .text + 0

000000000040 000200000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .text + f

Let's ignore the relocations from the .rela.eh_frame section because they are out of scope of this post. Instead, let’s try to understand the relocations from the .rela.text:

Offsetcolumn tells us exactly where in the target section (.textin this case) the fix/adjustment is needed. Note that these offsets are exactly the same as in our self-calculated monkey-patching above.Infois a combined value: the upper 32 bits — only 16 bits are shown in the output above — represent the index of the symbol in the symbol table, with respect to which the relocation is performed. In our example it is8and if we runreadelf --symbols obj.owe will see that it points to an entry corresponding to theadd5function. The lower 32 bits (4in our case) is a relocation type (seeTypebelow).Typedescribes the relocation type. This is a pseudo-column:readelfactually generates it from the lower 32 bits of theInfofield. Different relocation types have different formulas we need to apply to perform the relocation.Sym. Valuemay mean different things depending on the relocation type, but most of the time it is the symbol offset with respect to which we perform the relocation. The offset is calculated from the beginning of that symbol’s section.Addendis a constant we may need to use in the relocation formula. Depending on the relocation type, readelf actually adds the decoded symbol name to the output, so the column name isSym. Name + Addendabove but the actual field stores the addend only.

In a nutshell, these entries tell us that we need to patch the .text section at offsets 0x20 and 0x2d. To calculate what to put there, we need to apply the formula for the R_X86_64_PLT32 relocation type. Searching online, we can find different ELF specifications — like this one — which will tell us how to implement the R_X86_64_PLT32 relocation. The specification mentions that the result of this relocation is word32 — which is what we expect because callq arguments are 32 bit in our case — and the formula we need to apply is L + A - P, where:

Lis the address of the symbol, with respect to which the relocation is performed (add5in our case)Ais the constant addend (4in our case)Pis the address/offset, where we store the result of the relocation

When the relocation formula references some symbol addresses or offsets, we should use the actual — runtime in our case — addresses in the calculations. For example, we will be using text_runtime_base + 0x2d as P for the second relocation and not just 0x2d. So let's try to implement this relocation logic in our object loader:

loader.c:

...

/* from https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11.6/source/arch/x86/include/asm/elf.h#L51 */

#define R_X86_64_PLT32 4

...

static uint8_t *section_runtime_base(const Elf64_Shdr *section)

{

const char *section_name = shstrtab + section->sh_name;

size_t section_name_len = strlen(section_name);

/* we only mmap .text section so far */

if (strlen(".text") == section_name_len && !strcmp(".text", section_name))

return text_runtime_base;

fprintf(stderr, "No runtime base address for section %s\n", section_name);

exit(ENOENT);

}

static void do_text_relocations(void)

{

/* we actually cheat here - the name .rela.text is a convention, but not a

* rule: to figure out which section should be patched by these relocations

* we would need to examine the rela_text_hdr, but we skip it for simplicity

*/

const Elf64_Shdr *rela_text_hdr = lookup_section(".rela.text");

if (!rela_text_hdr) {

fputs("Failed to find .rela.text\n", stderr);

exit(ENOEXEC);

}

int num_relocations = rela_text_hdr->sh_size / rela_text_hdr->sh_entsize;

const Elf64_Rela *relocations = (Elf64_Rela *)(obj.base + rela_text_hdr->sh_offset);

for (int i = 0; i < num_relocations; i++) {

int symbol_idx = ELF64_R_SYM(relocations[i].r_info);

int type = ELF64_R_TYPE(relocations[i].r_info);

/* where to patch .text */

uint8_t *patch_offset = text_runtime_base + relocations[i].r_offset;

/* symbol, with respect to which the relocation is performed */

uint8_t *symbol_address = section_runtime_base(§ions[symbols[symbol_idx].st_shndx]) + symbols[symbol_idx].st_value;

switch (type)

{

case R_X86_64_PLT32:

/* L + A - P, 32 bit output */

*((uint32_t *)patch_offset) = symbol_address + relocations[i].r_addend - patch_offset;

printf("Calculated relocation: 0x%08x\n", *((uint32_t *)patch_offset));

break;

}

}

}

static void parse_obj(void)

{

...

/* copy the contents of `.text` section from the ELF file */

memcpy(text_runtime_base, obj.base + text_hdr->sh_offset, text_hdr->sh_size);

do_text_relocations();

/* make the `.text` copy readonly and executable */

if (mprotect(text_runtime_base, page_align(text_hdr->sh_size), PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC)) {

...

}

...

We are now calling the do_text_relocations function before marking our .text copy executable. We have also added some debugging output to inspect the result of the relocation calculations. Let's try it out:

$ gcc -o loader loader.c

$ ./loader

Calculated relocation: 0xffffffdc

Calculated relocation: 0xffffffcf

Executing add5...

add5(42) = 47

Executing add10...

add10(42) = 52

Great! Our imported code works as expected now. By following the relocation hints left for us by the compiler, we've got the same results as in our monkey-patching calculations in the beginning of this post. Our relocation calculations also involved text_runtime_base address, which is not available at compile time. That's why the compiler could not calculate the callq arguments in the first place and had to emit the relocations instead.

Handling constant data and global variables

So far, we have been dealing with object files containing only executable code with no state. That is, the imported functions could compute their output solely based on the inputs. Let's see what happens if we add some constant data and global variables dependencies to our imported code. First, we add some more functions to our obj.o:

obj.c:

...

const char *get_hello(void)

{

return "Hello, world!";

}

static int var = 5;

int get_var(void)

{

return var;

}

void set_var(int num)

{

var = num;

}

get_hello returns a constant string and get_var/set_var get and set a global variable respectively. Next, let's recompile the obj.o and run our loader:

$ gcc -c obj.c

$ ./loader

Calculated relocation: 0xffffffdc

Calculated relocation: 0xffffffcf

No runtime base address for section .rodata

Looks like our loader tried to process more relocations but could not find the runtime address for .rodata section. Previously, we didn't even have a .rodata section, but it was added now because our obj.o needs somewhere to store the constant string Hello, world!:

$ readelf --sections obj.o

There are 13 section headers, starting at offset 0x478:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000040

000000000000005f 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 1

[ 2] .rela.text RELA 0000000000000000 00000320

0000000000000078 0000000000000018 I 10 1 8

[ 3] .data PROGBITS 0000000000000000 000000a0

0000000000000004 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 4

[ 4] .bss NOBITS 0000000000000000 000000a4

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 1

[ 5] .rodata PROGBITS 0000000000000000 000000a4

000000000000000d 0000000000000000 A 0 0 1

[ 6] .comment PROGBITS 0000000000000000 000000b1

000000000000001d 0000000000000001 MS 0 0 1

[ 7] .note.GNU-stack PROGBITS 0000000000000000 000000ce

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[ 8] .eh_frame PROGBITS 0000000000000000 000000d0

00000000000000b8 0000000000000000 A 0 0 8

[ 9] .rela.eh_frame RELA 0000000000000000 00000398

0000000000000078 0000000000000018 I 10 8 8

[10] .symtab SYMTAB 0000000000000000 00000188

0000000000000168 0000000000000018 11 10 8

[11] .strtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 000002f0

000000000000002c 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[12] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00000410

0000000000000061 0000000000000000 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

l (large), p (processor specific)

We also have more .text relocations:

$ readelf --relocs obj.o

Relocation section '.rela.text' at offset 0x320 contains 5 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

000000000020 000a00000004 R_X86_64_PLT32 0000000000000000 add5 - 4

00000000002d 000a00000004 R_X86_64_PLT32 0000000000000000 add5 - 4

00000000003a 000500000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .rodata - 4

000000000046 000300000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .data - 4

000000000058 000300000002 R_X86_64_PC32 0000000000000000 .data - 4

...

The compiler emitted three more R_X86_64_PC32 relocations this time. They reference symbols with index 3 and 5, so let's find out what they are:

$ readelf --symbols obj.o

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 15 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000000000 0 FILE LOCAL DEFAULT ABS obj.c

2: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 1

3: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 3

4: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 4

5: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 5

6: 0000000000000000 4 OBJECT LOCAL DEFAULT 3 var

7: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 7

8: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 8

9: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 6

10: 0000000000000000 15 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 add5

11: 000000000000000f 36 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 add10

12: 0000000000000033 13 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 get_hello

13: 0000000000000040 12 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 get_var

14: 000000000000004c 19 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 set_var

Entries 3 and 5 don't have any names attached, but they reference something in sections with index 3 and 5 respectively. In the output of the section table above, we can see that the section with index 3 is .data and the section with index 5 is .rodata. For a refresher on the most common sections in an ELF file check out our previous post. To import our newly added code and make it work, we also need to map .data and .rodata sections in addition to the .text section and process these R_X86_64_PC32 relocations.

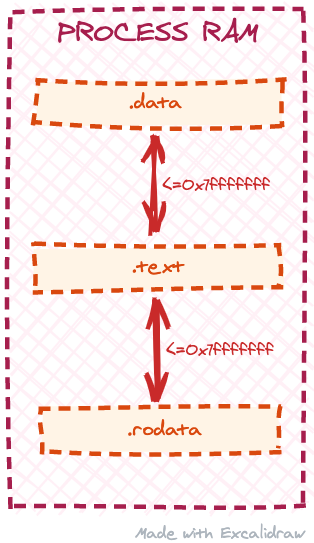

There is one caveat though. If we check the specification, we'll see that R_X86_64_PC32 relocation produces a 32-bit output similar to the R_X86_64_PLT32 relocation. This means that the "distance" in memory between the patched position in .text and the referenced symbol has to be small enough to fit into a 32-bit value (1 bit for the positive/negative sign and 31 bits for the actual data, so less than 2147483647 bytes). Our loader program uses mmap system call to allocate memory for the object section copies, but mmap may allocate the mapping almost anywhere in the process address space. If we modify the loader program to call mmap for each section separately, we may end up having .rodata or .data section mapped too far away from the .text section and will not be able to process the R_X86_64_PC32 relocations. In other words, we need to ensure that .data and .rodata sections are located relatively close to the .text section at runtime:

One way to achieve that would be to allocate the memory we need for all the sections with one mmap call. Then, we’d break it in chunks and assign proper access permissions to each chunk. Let's modify our loader program to do just that:

loader.c:

...

/* runtime base address of the imported code */

static uint8_t *text_runtime_base;

/* runtime base of the .data section */

static uint8_t *data_runtime_base;

/* runtime base of the .rodata section */

static uint8_t *rodata_runtime_base;

...

static void parse_obj(void)

{

...

/* find the `.text` entry in the sections table */

const Elf64_Shdr *text_hdr = lookup_section(".text");

if (!text_hdr) {

fputs("Failed to find .text\n", stderr);

exit(ENOEXEC);

}

/* find the `.data` entry in the sections table */

const Elf64_Shdr *data_hdr = lookup_section(".data");

if (!data_hdr) {

fputs("Failed to find .data\n", stderr);

exit(ENOEXEC);

}

/* find the `.rodata` entry in the sections table */

const Elf64_Shdr *rodata_hdr = lookup_section(".rodata");

if (!rodata_hdr) {

fputs("Failed to find .rodata\n", stderr);

exit(ENOEXEC);

}

/* allocate memory for `.text`, `.data` and `.rodata` copies rounding up each section to whole pages */

text_runtime_base = mmap(NULL, page_align(text_hdr->sh_size) + page_align(data_hdr->sh_size) + page_align(rodata_hdr->sh_size), PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

if (text_runtime_base == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("Failed to allocate memory");

exit(errno);

}

/* .data will come right after .text */

data_runtime_base = text_runtime_base + page_align(text_hdr->sh_size);

/* .rodata will come after .data */

rodata_runtime_base = data_runtime_base + page_align(data_hdr->sh_size);

/* copy the contents of `.text` section from the ELF file */

memcpy(text_runtime_base, obj.base + text_hdr->sh_offset, text_hdr->sh_size);

/* copy .data */

memcpy(data_runtime_base, obj.base + data_hdr->sh_offset, data_hdr->sh_size);

/* copy .rodata */

memcpy(rodata_runtime_base, obj.base + rodata_hdr->sh_offset, rodata_hdr->sh_size);

do_text_relocations();

/* make the `.text` copy readonly and executable */

if (mprotect(text_runtime_base, page_align(text_hdr->sh_size), PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC)) {

perror("Failed to make .text executable");

exit(errno);

}

/* we don't need to do anything with .data - it should remain read/write */

/* make the `.rodata` copy readonly */

if (mprotect(rodata_runtime_base, page_align(rodata_hdr->sh_size), PROT_READ)) {

perror("Failed to make .rodata readonly");

exit(errno);

}

}

...

Now that we have runtime addresses of .data and .rodata, we can update the relocation runtime address lookup function:

loader.c:

...

static uint8_t *section_runtime_base(const Elf64_Shdr *section)

{

const char *section_name = shstrtab + section->sh_name;

size_t section_name_len = strlen(section_name);

if (strlen(".text") == section_name_len && !strcmp(".text", section_name))

return text_runtime_base;

if (strlen(".data") == section_name_len && !strcmp(".data", section_name))

return data_runtime_base;

if (strlen(".rodata") == section_name_len && !strcmp(".rodata", section_name))

return rodata_runtime_base;

fprintf(stderr, "No runtime base address for section %s\n", section_name);

exit(ENOENT);

}

And finally we can import and execute our new functions:

loader.c:

...

static void execute_funcs(void)

{

/* pointers to imported functions */

int (*add5)(int);

int (*add10)(int);

const char *(*get_hello)(void);

int (*get_var)(void);

void (*set_var)(int num);

...

printf("add10(%d) = %d\n", 42, add10(42));

get_hello = lookup_function("get_hello");

if (!get_hello) {

fputs("Failed to find get_hello function\n", stderr);

exit(ENOENT);

}

puts("Executing get_hello...");

printf("get_hello() = %s\n", get_hello());

get_var = lookup_function("get_var");

if (!get_var) {

fputs("Failed to find get_var function\n", stderr);

exit(ENOENT);

}

puts("Executing get_var...");

printf("get_var() = %d\n", get_var());

set_var = lookup_function("set_var");

if (!set_var) {

fputs("Failed to find set_var function\n", stderr);

exit(ENOENT);

}

puts("Executing set_var(42)...");

set_var(42);

puts("Executing get_var again...");

printf("get_var() = %d\n", get_var());

}

...

Let's try it out:

$ gcc -o loader loader.c

$ ./loader

Calculated relocation: 0xffffffdc

Calculated relocation: 0xffffffcf

Executing add5...

add5(42) = 47

Executing add10...

add10(42) = 52

Executing get_hello...

get_hello() = ]�UH��

Executing get_var...

get_var() = 1213580125

Executing set_var(42)...

Segmentation fault

Uh-oh! We forgot to implement the new R_X86_64_PC32 relocation type. The relocation formula here is S + A - P. We already know about A and P. As for S (quoting from the spec):

“the value of the symbol whose index resides in the relocation entry"

In our case, it is essentially the same as L for R_X86_64_PLT32. We can just reuse the implementation and remove the debug output in the process:

loader.c:

...

/* from https://elixir.bootlin.com/linux/v5.11.6/source/arch/x86/include/asm/elf.h#L51 */

#define R_X86_64_PC32 2

#define R_X86_64_PLT32 4

...

static void do_text_relocations(void)

{

/* we actually cheat here - the name .rela.text is a convention, but not a

* rule: to figure out which section should be patched by these relocations

* we would need to examine the rela_text_hdr, but we skip it for simplicity

*/

const Elf64_Shdr *rela_text_hdr = lookup_section(".rela.text");

if (!rela_text_hdr) {

fputs("Failed to find .rela.text\n", stderr);

exit(ENOEXEC);

}

int num_relocations = rela_text_hdr->sh_size / rela_text_hdr->sh_entsize;

const Elf64_Rela *relocations = (Elf64_Rela *)(obj.base + rela_text_hdr->sh_offset);

for (int i = 0; i < num_relocations; i++) {

int symbol_idx = ELF64_R_SYM(relocations[i].r_info);

int type = ELF64_R_TYPE(relocations[i].r_info);

/* where to patch .text */

uint8_t *patch_offset = text_runtime_base + relocations[i].r_offset;

/* symbol, with respect to which the relocation is performed */

uint8_t *symbol_address = section_runtime_base(§ions[symbols[symbol_idx].st_shndx]) + symbols[symbol_idx].st_value;

switch (type)

{

case R_X86_64_PC32:

/* S + A - P, 32 bit output, S == L here */

case R_X86_64_PLT32:

/* L + A - P, 32 bit output */

*((uint32_t *)patch_offset) = symbol_address + relocations[i].r_addend - patch_offset;

break;

}

}

}

...

Now we should be done. Another try:

$ gcc -o loader loader.c

$ ./loader

Executing add5...

add5(42) = 47

Executing add10...

add10(42) = 52

Executing get_hello...

get_hello() = Hello, world!

Executing get_var...

get_var() = 5

Executing set_var(42)...

Executing get_var again...

get_var() = 42

This time we can successfully import functions that reference static constant data and global variables. We can even manipulate the object file’s internal state through the defined accessor interface. As before, the complete source code for this post is available on GitHub.

In the next post, we will look into importing and executing object code with references to external libraries. Stay tuned!